From Neuchatel, the guide to the Trans Swiss Trail recommends to take a boat across the lake. This would bring the walker to the village of Cuderfin, to be followed by a short walk northwards to La Sauge before heading eastwards to Mont Vully. However, I had two problems with this proposed route. On a practical level, the boats were not running until much later in the day, and on a much reduced schedule. I was not keen on waiting until late in the morning, or even early afternoon, to start my walk. But on a deeper level, I had reservations about taking the ferry across the lake. A walker walks, and my plan was to follow the trail as a walking route through its entirety.

With all of this in mind, I decided to walk around the shore of Lac de Neuchâtel, cross over the Canal de la Thielle, and re-join the official trail at La Sauge. It would make the walk considerably longer, but I would avoid the wait for a ferry, and I would maintain the integrity of the trail as a purely walking route.

I did not expect to make that trek very soon after my last stage of the Trans Swiss Trail, but the weather improved so dramatically, that by the middle of the week, I was giving it serious thought. The sub-zero temperatures of the last weekend were gone, replaced by warmth that by Friday had reached +15˚C. The weekend was forecast to be a little cooler, but only by a degree or two, and with sunshine into the bargain.

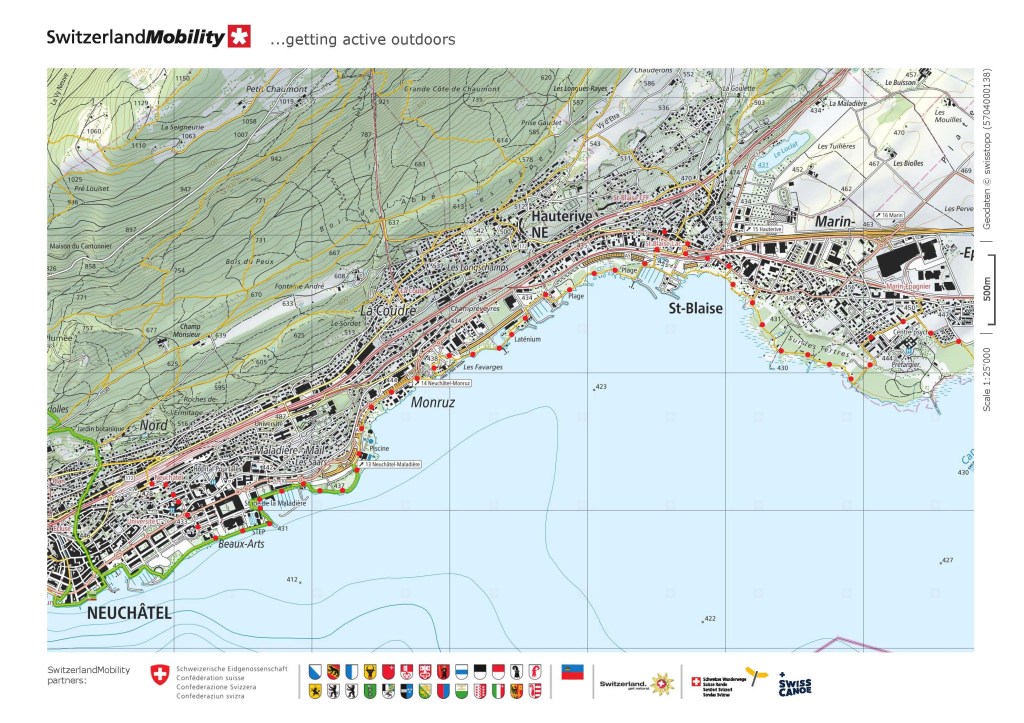

And that is how I came to do some hasty preparation: printing out of maps, organising train connections, and preparing my rucksack. I was ready for a long walk on Sunday. I arrived in Neuchâtel early in the morning and made my way towards the lake shore. On the way, I passed the Basilique Notre-Dame de l’Assomption (Basilica of Our Lady of the Assumption), which is known colloquially as “The Red Church”. It is a modern construct, having been built between 1906 and 1912. The construction used artificial stone, tinted red to look like the red sandstone of Alsace and the northern Jura. I did not go in, but kept on my way, and soon I was walking along the lake shore.

Being sandwiched between the mountains to the west and the lake to the east, the city of Neuchâtel has no way to spread out except to north and south. As a result, the lake shore was a suburban environment for most of my route. I walked past middle class neighbourhoods, factories, and commercial centres. There was occasional parkland, as well as marinas on the lake itself. But even in such uninteresting circumstances, one can still find the occasional object of interest. The Swiss have realised that insects, while individually undesirable, collectively play an essential part in the world’s ecosystems. And to help the insects survive through freezing winters, many Swiss will have an “insect hotel” on their property, just as in other countries it is common to have a bird feeder. These insect hotels consist of wood, perforated with holes of varying sizes, sometimes natural, sometimes man-made, but all to allow the insects hibernate through the winter. And there, by the shores of Lac de Neuchâtel was the largest insect hotel I have seen in Switzerland.

But for the most part, it was a case of just following the lake shore, availing of the parkland as much as possible. And so I came to St-Blaise. The Swiss have designated the village centre as Heritage Site, so I made a short detour to see it. I have to say that I was disappointed. Yes, the village has plenty of old buildings centred on the village church, but they are no better than so many other Swiss towns and villages. In the church itself, the service was in progress when I got there, so I did not go in. It would be churlish to act the tourist while people are at worship.

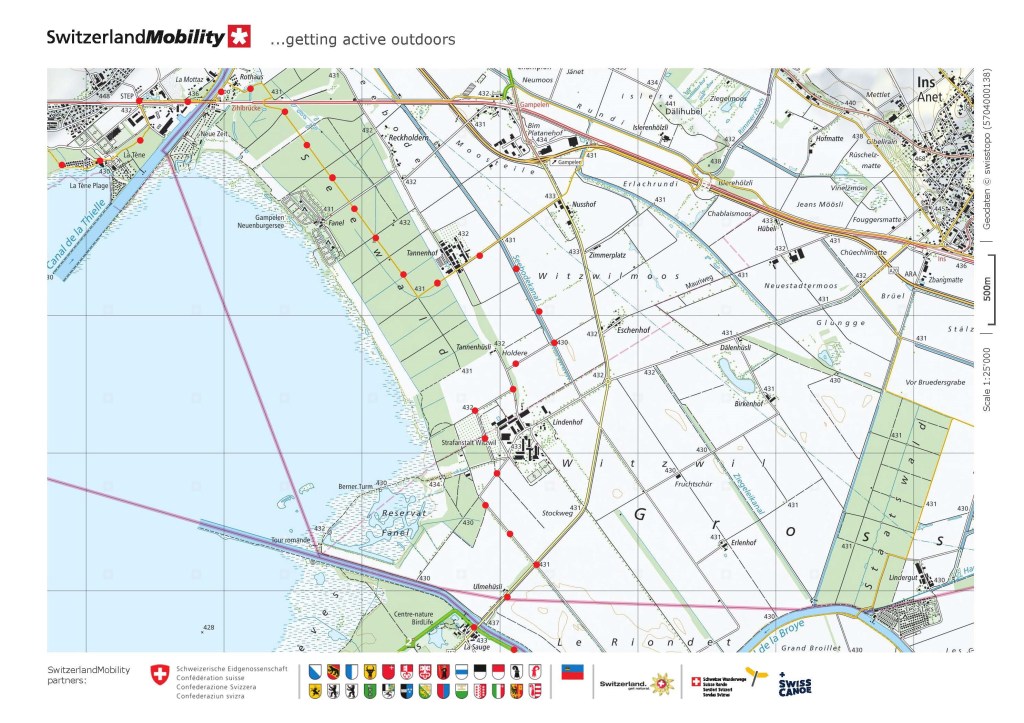

Shortly after St-Blaise, on the northern shore of the lake, I eventually reached the Canal de la Thielle. This is part of a construction referred to as the Jura Water Correction. Over the centuries, the lakes of Neuchâtel, Biel and Murten, as well as the rivers feeding them, had been prone to flooding. In the 1840s, a proposal was put forward to regulate the water flow into and between the lakes. But at that time, Switzerland was a loose confederation without the central cohesion to manage such a project. But after the adoption of the first national Swiss constitution in 1848, work began on the project in the 1860s. As well as weirs and dams on the river Aare, the work also included the construction of two canals. One of these turned the river Thielle into a canal. The Thielle links Lac de Neuchâtel to the Bielersee (Lac de Bienne). It is a canal without locks, allowing water to flow freely between the two lakes.

The Canal de la Thielle is at the north-west corner of the lake, and from there, I was following the north shore eastwards. This part of the route is a bit less urban than the stretch between Neuchâtel and St-Blaise. There is more woodland, and where houses line the shore, many are holiday chalets, sitting comfortably in this quiet environment. Or maybe I was just lucky to be going that way at this time of the year before the tourists arrive.

Approaching the north-east corner of the lake, I had to make some detours through farmland to get to the second of my canals on the route, the Canal de la Broye. This is also part of the Jura Water Correction, and links the Murtensee (Lac de Morat) to the Lac de Neuchâtel. The river Broye was a small waterflow linking the two lakes, and as part of the correction, it was turned into what is now a wide canal. Following the correction, the water levels in all three lakes decreased, as did the area of the water surface. Lac de Neuchâtel lost some 23 square kilometres of lake, while the Murtensee lost over 4 square kilometres. The average drop in the water level was 2.5 metres. In the case of the Lac de Neuchâtel, much of the newly created land was kept as wetlands and nature reserves.

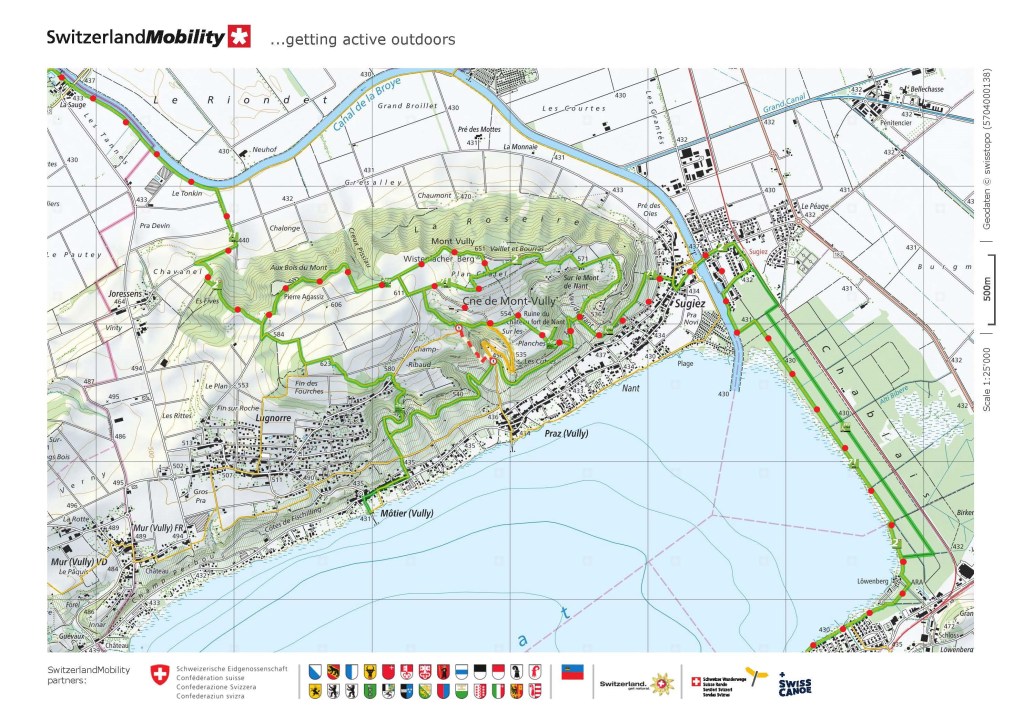

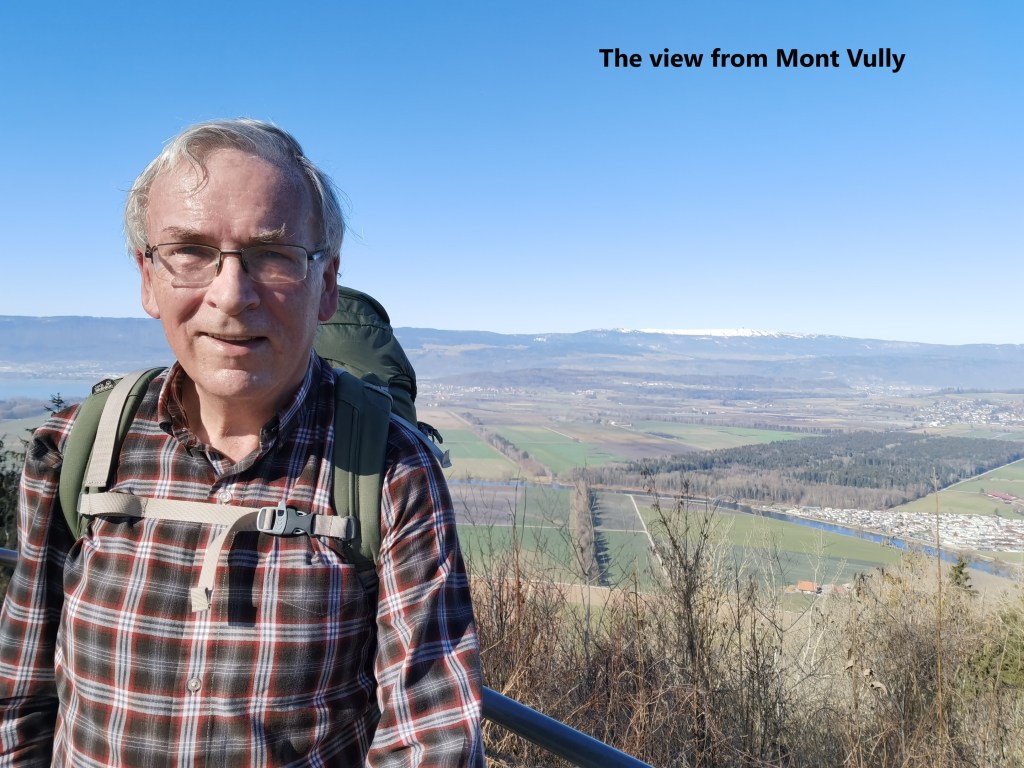

At the Canal de la Broye, I turned away from the Lac de Neuchâtel, heading eastwards along the southern canal bank. I was now back on the official Trans Swiss Trail route, on the way to Mont Vully. The trail soon left the canal and wound its way up the slopes of Mont Vully, affording a look back towards Lac de Neuchâtel and the city on the other side. Mont Vully has a few curiosities and one of them is on the way to the summit. It is called the Pierre Agassiz. It is what is called a geological erratic, a massive stone 10m long and 4m high. that is out of place geologically relative to its surroundings. While Mont Vully is made of Limestone, the Pierre Agassiz is a type called eyed gneiss. At some time during the ice age, this stone fell onto a glacier, and was carried along for more than 100km as the glacier moved. At some stage, with the melting of the glaciers, the stone was deposited here on Mont Vully. It is named after a local scientist, Louis Agassiz, who was one of the first to develop theories around glacial movement. There are of course local legends about how it got here, probably more exciting than the glacial explanation.

Mont Vully is not especially high, only about 200m above the surrounding countryside, but its isolated elevation provides amazing views all around. On the one side, from the summit, it is possible to see much of the Jura chain to the west, while to the south east, the Alps are visible.

On the descent from Mont Vully, I made a short detour to visit one of the other curiosities on the mountain. A little way off the trail is the Tour des Sarrasins. This is a ruin from an ancient tower on the mountainside. The tower is thought to have been built in the 12th or 13th century, though nothing is certain about its origin. It is mentioned in maps from 1772, where it is simply referred to as “Ancient Tower”. Very little remains. The destruction of the tower, like its origins, has not been documented. Even the name, Sarrasins, means buckwheat, so how it came to get its name is lost in the mysteries of the place.

I continued making my dawn from Mont Vully, through vineyards filled with rows of bare vines, waiting for the summer sun. Soon, I came to the village of Sugiez, and crossed back over the Canal de la Broye.

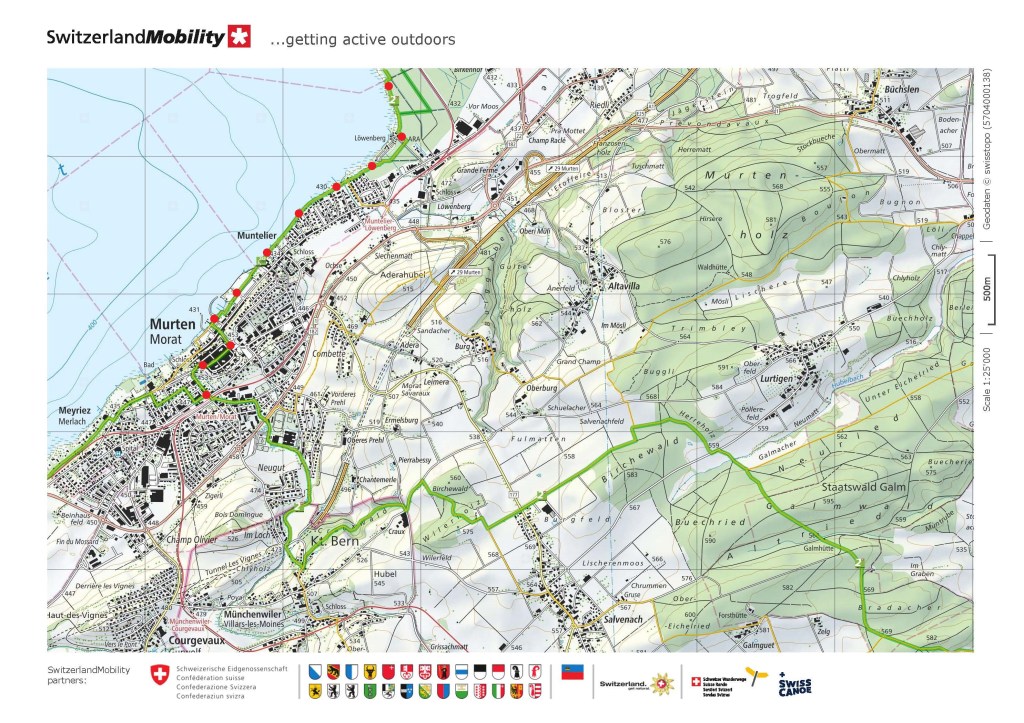

I had crossed this same canal before at the same place, when I was walking the Jakobsweg from Basel to Moudon. That time, I had reached Sugiez by a different route, but then as now, I was on my way to Murten. It meant that I was not on familiar ground. I hardly needed the map at all, quickly making my way through the Chablais woods, and turning southwards on reaching the camping site at Löwenberg. As I continued through Muntelier, there seemed to be a lot of people out and about, which in these times of coronavirus and Covid-19 makes me a little nervous. Much of the lakeshore is tall reed beds, but I did at last find a spot where I could look back across the Murtensee towards Mont Vully.

The crowds increased still more as I came closer to Murten, so I left the lake shore, and took to the road. A short distance up the hill then brought me to the town gates. The name of Murten is indelibly inscribed into Swiss history. The early Swiss confederation was invaded twice in 1476 by the Duke of Burgundy. On the first occasion, the Swiss sent him packing at the battle of Grandson, but he reassembled his army at Lausanne and came back in June 1476. He first laid siege to the little town of Murten. The Swiss rallied their troops and arrived at Murten on June 19th. Charles expected battle on the 21st, but the Swiss were waiting for an additional 4,000 men from Zurich canton. With heavy rain on June 22nd, 1476, Charles reckoned there would be no fighting that day. His army was mostly mercenaries, and he ordered that the men be paid, resulting in disorder in his camp. In the disorder, the Swiss attacked. The outer Burgundian positions were quickly overrun. Charles tried to rally his men, and for a time, the fate of the battle was in the balance. But each mustered Burgundian defence failed, and Charles ordered a retreat, which soon became a rout. For several miles along the lake shore, the Swiss pursued the Burgundians, attacking and giving no quarter to any stragglers. The result was complete destruction of the Burgundian army. It was a defining moment in the formation of a Swiss national identity.

But when I came to Murten, the sun was out, and the people too. In these strange time, shops were only selling takeaway refreshments, and almost all seemed to have a queue outside. I didn’t stop, but made my way, on through the town, and down to the railway station for my train back to Basel.

This was a long walk. My total step count for the day was 52,371. That is somewhere close to 35 kilometres.